Registering properties

So far, you learned how to register classes and functions. This is already powerful enough to create simple applications with godot-rust, however you might want to give Godot more direct access to the state of your object.

This is where properties come into play. In Rust, properties are typically defined as fields of a struct.

See also GDScript reference for properties.

Table of contents

- Registering variables

- Exporting variables

- Enums

- Advanced usage

- Custom types with

#[var]and#[export]

Registering variables

Previously, we defined a function Monster::get_name(). This works to fetch the name, but requires you to write obj.get_name() in GDScript.

Sometimes, you do not need this extra encapsulation and would like to access the field directly.

The godot-rust library provides an attribute #[var] to annotate fields that should be exposed as variables. This works like the var keyword in

GDScript.

Starting with the earlier struct declaration, we now add the #[var] attribute to the name field. We also change the type from String to

GString, since this field is now directly interfacing Godot.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[derive(GodotClass)] #[class(init, base=Node3D)] struct Monster { #[var] name: GString, hitpoints: i32, } }

The effect of this is that name is now registered as a property in Godot:

var monster = Monster.new()

# Write the property.

monster.name = "Orc"

# Read the property.

print(monster.name) # prints "Orc"

In GDScript, properties are syntactic sugar for function calls to getters and setters. You can also do so explicitly:

var monster = Monster.new()

# Write the property.

monster.set_name("Orc")

# Read the property.

print(monster.get_name()) # prints "Orc"

The #[var] attribute also takes parameters to customize whether both getters and setters are provided, and what their names are. You can

also write Rust methods acting as getters and setters, if you have more involved logic. See the API documentation for details.

Like #[func] functions, #[var] fields do not need to be pub. This separates visibility towards Godot and towards Rust.

In practice, you can still access #[var] fields from Rust, but via detours (e.g. Godot's reflection APIs). But this is then a deliberate

choice; private fields are primarily preventing accidental mistakes or encapsulation breaches.

Exporting variables

The #[var] attribute exposes a field to GDScript, but does not display it in the Godot editor UI.

Making a property available to the editor is called exporting. Like the GDScript annotation @export, godot-rust provides exports through the

#[export] attribute. You might see a pattern with naming here.

The following code not only makes the name field available to GDScript, but it also adds a property UI in the editor. This allows you to

name every Monster instance individually, without any code!

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[derive(GodotClass)] #[class(init, base=Node3D)] struct Monster { #[export] name: GString, hitpoints: i32, } }

You may have noticed that there is no longer a #[var] attribute. This is because #[export] always implies #[var] -- the name is still

accessible from GDScript like before.

You can also declare both attributes on the same field. This is in fact necessary as soon as you provide arguments to customize them.

Enums

You can export Rust enums as properties, as long as they are C style enums (no associated data per variant). An exported enum appears as a drop-down field in the editor, with all available options. In order to do that, you need to derive three traits:

GodotConvertto define how the type is converted from/to Godot.Varto allow using it as a#[var]property, so it can be accessed from Godot.Exportto allow using it as a#[export]property, so it appears in the editor UI.

Additionally, it can make sense to derive following standard traits:

Clone: it is possible without, but then you need to implementVarmanually. The reason is thatVaralso provides Rust getters when used with#[var(pub)], which require cloning the value.Default: if there is a meaningful default value. If not, use#[init(val = ...)]on the field declarations to provide an initial value.

Godot does not have dedicated enum types, so you can map them either as integers (e.g. i64) or strings (GString). This can be

configured using the via key of the #[godot] attribute.

Exporting an enum can be done as follows:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[derive(GodotConvert, Var, Export, Default, Clone)] #[godot(via = GString)] pub enum Planet { #[default] // Rust standard attribute, not godot-rust. Earth, Mars, Venus, } #[derive(GodotClass)] #[class(base=Node)] pub struct SpaceFarer { #[export] favorite_planet: Planet, } }

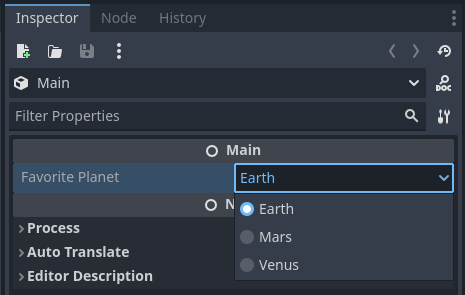

The above will show up as follows in the editor UI:

Refactoring the Rust enum may impact already serialized scenes, so be mindful if you want to choose integers or strings as the underlying representation:

- Integers enable renaming variants without breaking existing scenes, however new ones must be strictly added at the end, and existing ones cannot be removed or reordered.

- Strings allow free reordering and removing (if unused) and make debugging easier. However, you cannot rename them, and they take slightly more space (only relevant if you have tens of thousands).

Of course, it is always possible to adjust existing scene files, but this involves manual search&replace and is generally error-prone.

Enums are not first-class citizens in Godot. Even if you define them in GDScript, they are mostly syntactic sugar for constants. This declaration:

enum Planet {

EARTH,

VENUS,

MARS,

}

@export var favorite_planet: Planet

is roughly the same as:

const Planet: Dictionary = {

EARTH = 0,

VENUS = 1,

MARS = 2,

}

@export_enum("EARTH", "VENUS", "MARS") var favorite_planet = Planet.EARTH

However, the enum is not type-safe, you can just do this:

var p: Planet = 5

Furthermore, you can also not easily retrieve the name "EARTH" from the expression Planet.EARTH.1

See GDScript enums for more details.

Advanced usage

Both #[var] and #[export] attributes accept parameters to further customize how properties are registered in Godot.

Consult the API documentation for details.

Packed*Array types use copy-on-write semantics, meaning every new instance can be considered an independent copy. When a Rust-side packed

array is registered as a property, GDScript will create a new instance of the array when you mutate it, making changes invisible to Rust code.

There is a GitHub issue with more details.

Instead, use Array<T> or register designated #[func] methods that perform the mutation on Rust side.

Custom types with #[var] and #[export]

If you want to register properties of user-defined types, so they become accessible from GDScript code (#[var]) or additionally from the

editor (#[export]), then you can implement the Var and Export traits, respectively.

These traits also come with derive macros, #[derive(Var)] and #[derive(Export)].

Enabling all sorts of types for Var and Export seems convenient, but keep in mind that your conversion functions are invoked every time

the engine accesses the property, which may sometimes be behind the scenes. Especially for #[export] fields, interactions with the editor UI

or serialization to/from scene files can cause a quite a bit of traffic.

As a general rule, try to stay close to Godot's own types, e.g. Array, Dictionary or Gd. These are reference-counted or simple pointers.

Footnotes

You can obtain "EARTH" if you iterate the Planet dictionary and compare each value (assuming there are no duplicates).

That however requires that you know the type (Planet); the value itself does not hold this information.