Game architecture

This chapter assumes that you are developing a game with Godot and Rust; however, many of the points apply to other projects like simulations or visualizations.

For users new to the godot-rust binding, there are a few questions that almost always come up:

- How do I organize my Rust code the best way?

- Should I still use GDScript or do everything in Rust?

- Where should I write my game logic?

- How can I use the Godot scene tree, if Rust has no inheritance?

Regarding architecture, godot-rust offers a lot of freedom and does not force you into certain patterns. How much you want to develop in GDScript and how much in Rust, is entirely up to you. The choice may depend on your experience, the amount of existing code you already have in either language, the scope of your game or simply personal preference.

Each language has their own strengths and weaknesses:

- GDScript is close to the engine, allows for very fast prototyping and integrates well with the editor. However, its type system is limited and refactoring is often manual. There is no dependency management.

- Rust focuses on type safety, performance and scalability, with mature tooling and ecosystem. The language is rather complex and enforces discipline, and Godot-related tasks tend to be more verbose.

As a starting point, this chapter highlights three common patterns that have been successfully used with godot-rust. This does not mean you must adhere to any of them; depending upon your needs, hybrid solutions or entirely different designs are also worth considering. The three patterns are listed in ascending order with respect to complexity and scalability.

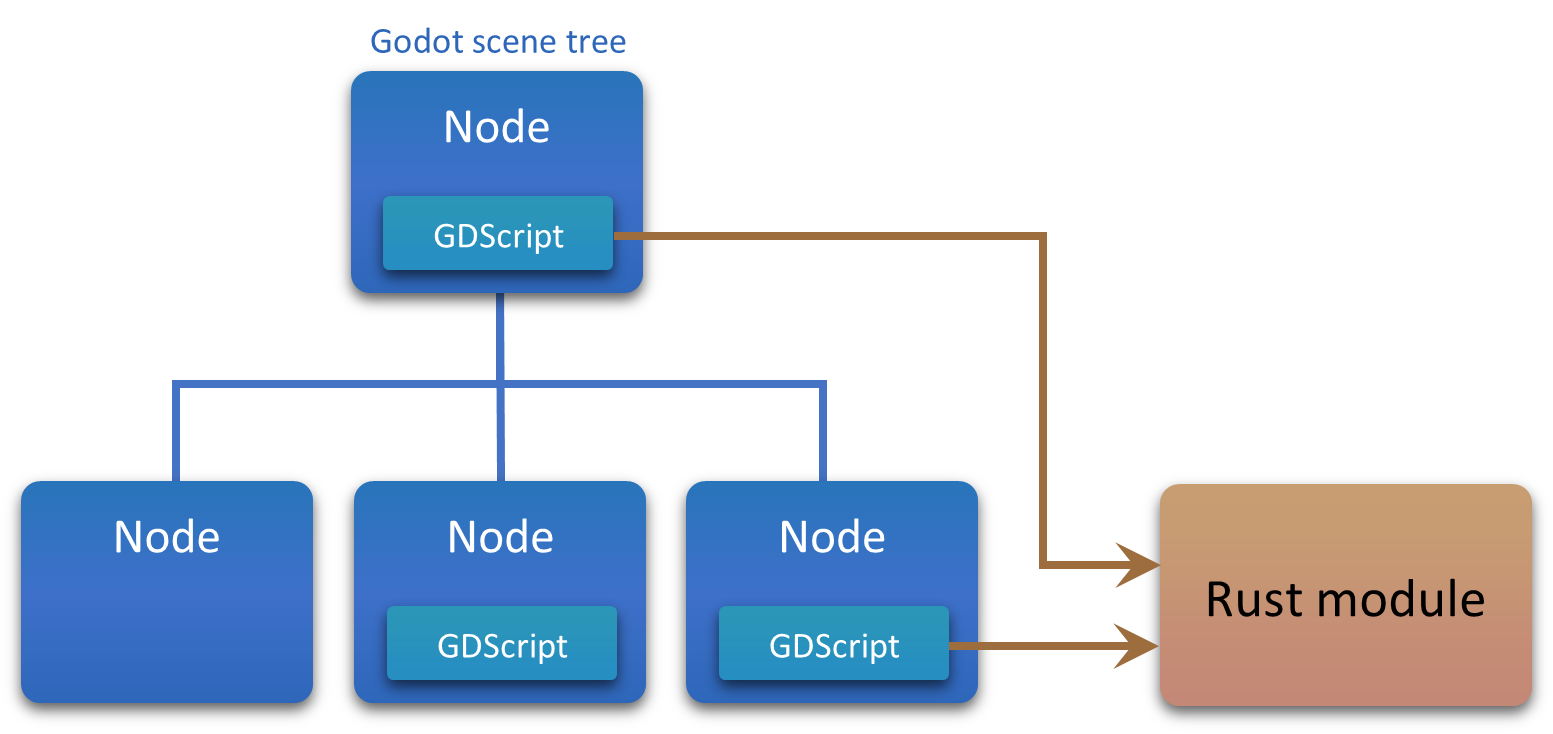

1. Godot game + Rust module

In this architecture, you develop your game primarily in the Godot engine. Most of the game logic resides in GDScript, and the Godot editor is your tool of choice.

During development, you encounter a feature which you wish to develop in Rust while making it accessible to GDScript. Reasons may include:

- The code is performance-critical and GDScript is not fast enough.

- There is a Rust-based library that you wish to use, for example pathfinding, AI, or physics.

- You have a segment of your code with high complexity that is difficult to manage in GDScript.

In this case, you can write a GDNative class in Rust, with an API that exposes precisely the functionality you need -- no more and no less. godot-rust is only needed at the interface with GDScript. There are no calls into Godot from your Rust code, only exported methods.

Pros:

- Very easy to get started, especially for existing Godot codebases.

- You can fully benefit from Godot's scene graph and the tooling around it.

- You can test the Rust functionality independently, without running Godot.

Cons:

- As most of the game logic is in GDScript, your project will not benefit from Rust's features, type safety and refactoring capabilities.

- Your game logic needs to fit Godot's scene graph model and you have little control about architecture.

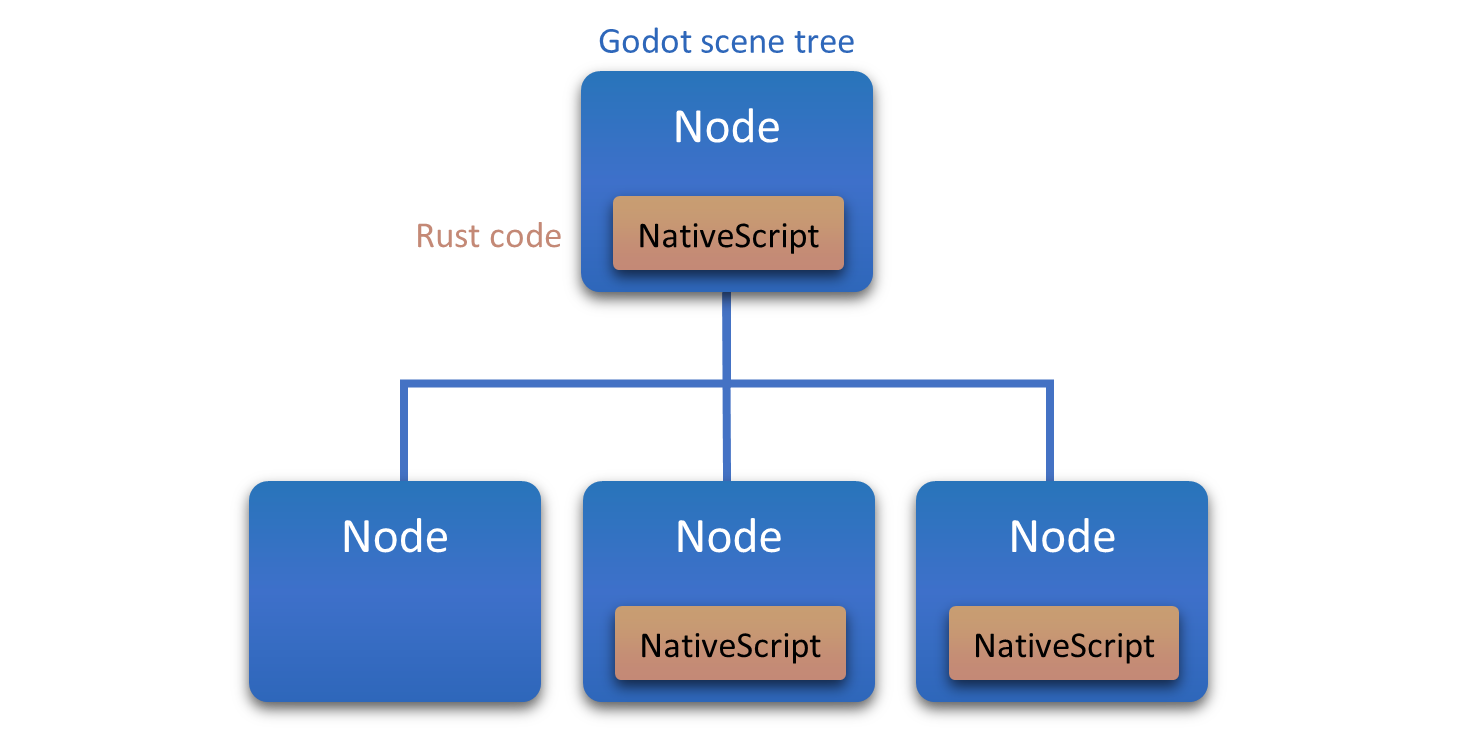

2. Godot scene tree + native scripts

The Godot engine encourages a certain pattern: each game entity is represented by a scene node, and the logic for each node is implemented in a GDScript file. You can follow the same architecture with godot-rust, the only difference being that scripts are implemented in Rust.

Instead of .gd script files, you use .rs files to implement native scripts, and you register native classes in .gdns files. Each Rust script can call into Godot to interact with other nodes, set up or invoke signals, query engine state, etc. Godot types have an equivalent representation in Rust, and the Object hierarchy is emulated in Rust via Deref trait -- this means that e.g. Node2D references can be used to invoke methods on their parent class Node.

It often makes sense to be pragmatic and not try to do everything in Rust. For example, tweaking parameters for particle emitters or animation works much better in GDScript and/or the Godot editor.

Pros:

- You can make full use of Godot's scene graph architecture while still writing the logic in Rust.

- Existing code and concepts from GDScript can be carried over quite easily.

Cons:

- You have little architectural freedom and are constrained by Godot's scene tree model.

- As godot-rust is used throughout your entire codebase, this will tightly couple your game logic to Godot. Testing and isolating functionality can be harder and you are more subject to version changes of Godot and godot-rust.

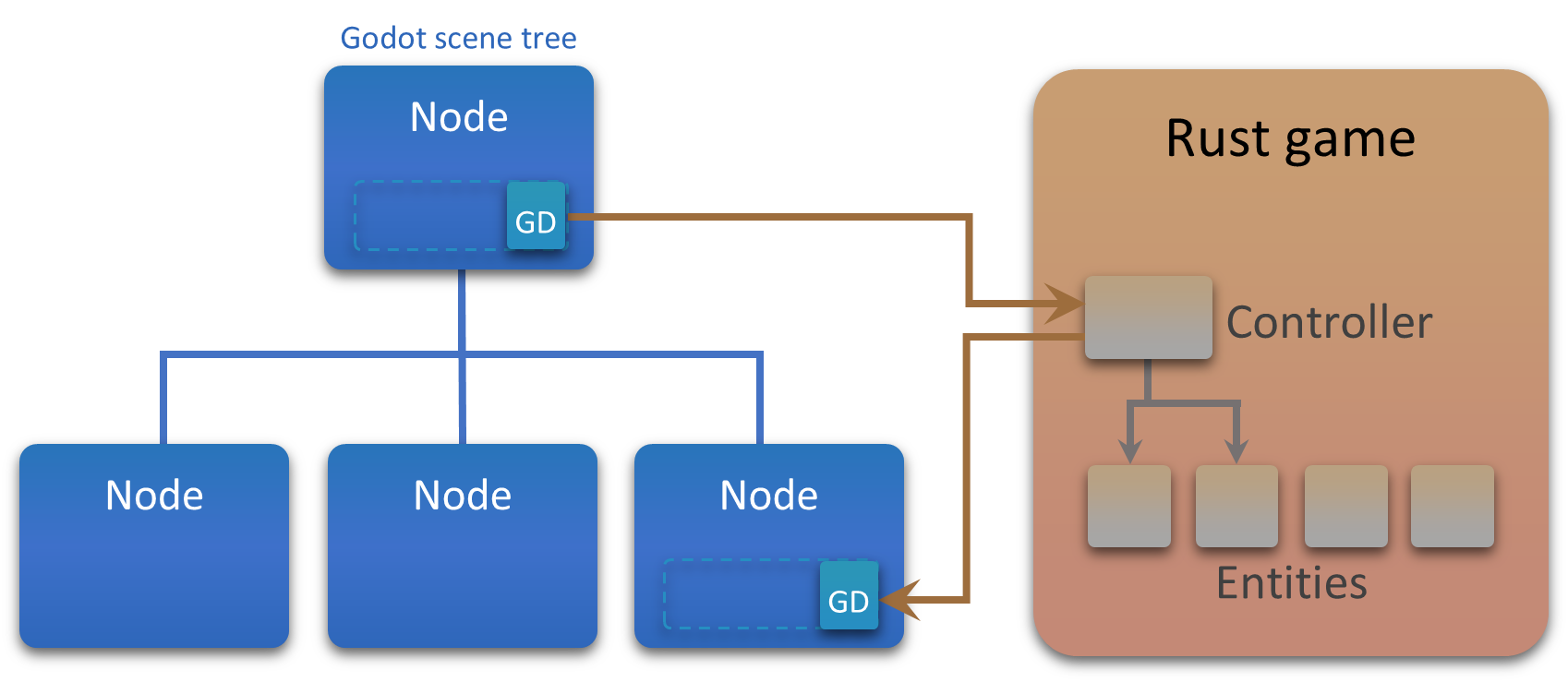

3. Rust game + Godot I/O layer

This architecture is the counterpart to section 1. Most of your game is written in Rust, and you use the engine primarily for input/output handling. You can have an entry point to your Rust library (the Controller) which coordinates the simulation.

A typical workflow is as follows:

- Input: You use the Godot engine to collect user input and events (key pressed, network packet arrived, timer elapsed, ...).

- Processing: The collected input is passed to Rust. The Controller runs a step in your game simulation and produces results.

- Output: These results are passed back to Godot and take effect in the scene (node positions, animations, sound effects, ...).

If you follow this pattern strictly, the Godot scene graph can be entirely derived from your Rust state, as such it is only a visualization. There will be some GDScript glue code to tweak graphics/audio output.

This can be the most scalable and "Rusty" workflow, but it also requires a lot of discipline. Several interactions, which the other workflows offer for free, need to be implemented manually.

Pros:

- You are completely free how you organize your Rust game logic. You can have your own entity hierarchy, use an ECS, or simply a few linear collections.

- As your game logic runs purely in Rust, you don't need Godot to run the simulation. This allows for the following:

- Rust-only headless server

- Rust-only unit and integration tests

- Different/simplified visualization backends

Cons:

- A robust design for your Rust architecture is a must, with considerable up-front work.

- You need to manually synchronize your Rust entities with the Godot scene tree. In many cases, this means duplication of state in Rust (e.g. tile coordinate + health) and in Godot (world position + healthbar), as well as mapping between the two.